Resisting Social Cleansing in Los Angeles: the Origins of the K3 Tenant Council (Alpine LA Properties)

If you were to ask the tenants at 249 South Avenue 55 to identify when they first discovered their collective power, they might point to an afternoon in late December, 2020, just as Los Angeles was becoming the global epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Matt DeBoth, a low-ranking property manager for their landlord—L.A.-based real estate investment firm Alpine LA Properties—was scheduled to meet with a longtime resident of the building about mold that had been accumulating in her carpet for over a decade. The tenant, a Latinx, Spanish-speaking mother, had lived in the building for over 20 years. DeBoth likely assumed the interaction would proceed the same way they had in the past: the tenant would grapple with the language barrier, attempting to demonstrate the severity of the situation, and DeBoth would minimize the issue, framing whatever superficial maintenance work he permitted as a rare and benevolent gift. The implicit message was always clear: Alpine LA Properties was happy to maintain dangerous, unlivable conditions in her home in the hopes that she and her family would self-evict. In all his interactions with the longtime residents of 249 South Avenue 55, DeBoth routinely deployed a favorite weapon of all landlords: isolation, atomization.

“Alpine LA Properties was happy to maintain dangerous, unlivable conditions in her home in the hopes that she and her family would self-evict.”

Instead of meeting with a single, isolated tenant that December afternoon, however, DeBoth encountered something very different. When he stepped foot into the open-air courtyard of the two-story building, he was met by a dozen tenants—longtime Latinx residents alongside younger white, Black, and Asian gentrifiers—masked, arms folded, standing in a broad semicircle.

The old carpet would be removed and a new one installed, they informed DeBoth. Today.

DeBoth did his best to maintain the upper hand, patronizing the tenants and “explaining” to them—in the almost pathologically upbeat tone he uses even when threatening people with eviction—that the carpet did not need to be replaced. He repeated this line even after maintenance workers had begun lifting the carpet, revealing large swathes of toxic black mold and extensive water damage from years of moisture seeping through the foundation. A minor issue, DeBoth insisted. The moldy, decades-old carpet could be lightly cleaned and then reinstalled—no need for a new one.

Whereas in the past this approach had succeeded against individual tenants, it failed against the collective power of an entire building. Surrounding DeBoth, recording every moment of the interaction, the Ave 55 tenants stood firm in their simple demand. The maintenance workers seemed to grasp intuitively that the power dynamic had shifted; without waiting for DeBoth’s approval, they stripped the carpet and hauled it to the dumpster. Chastened, DeBoth pivoted and spoke vaguely about a “fair price” for a replacement. But the writing was on the wall: Alpine LA Properties would pay to replace the carpet. The tenants, united in support of their neighbor, had won. And they had won not through the intervention of the housing department, or an elected official, or an attorney—options they had already exhausted, with few results. They achieved this small but meaningful victory using the weapon of organized solidarity and direct confrontation, asserting collectively what they needed and then seizing it.

At the end of the interaction, clinging to his position of authority, DeBoth had the gall to suggest that the tenant should consider her new carpet “an early Christmas gift from Alpine LA Properties.” She and her neighbors laughed him out of the front gate.

The Seeds of Solidarity: Meeting our neighbors, Acknowledging the violence we face

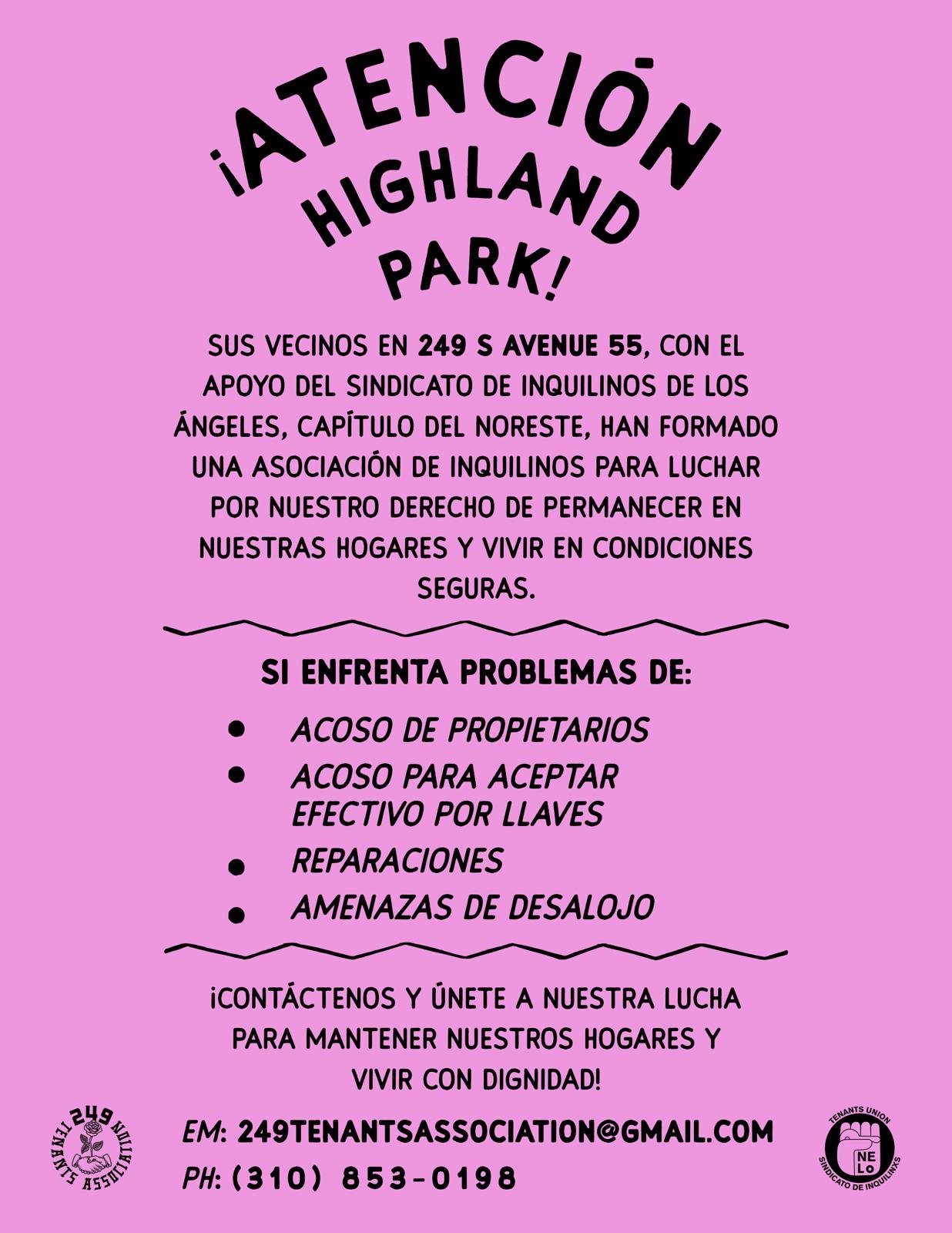

The tenants at 249 South Avenue 55, with the support of members of the L.A. Tenants Union’s Northeast Local, have organized themselves as the 249 South Avenue 55 Tenants Association. They didn’t always have the kind of solidarity they showed that December afternoon. The story of how they built and continue to build that power, and how that power contributes to and depends upon the broader tenant movement in Los Angeles, has much to teach us about:

the forms of autonomous organization and militant struggle tenants in L.A. are practicing in the fight against the violent social cleansing known as “gentrification,” and

the horizons of the tenant power movement, the new social relations and forms of solidarity that point to more liberating, celebratory, and communal ways of being together and reproducing our lives.

Members of LATU’s Northeast Local (NELo) met the Ave 55 tenants thanks to a communal practice developed in the summer of 2020, in the wake of the George Floyd uprisings. NELo members began conducting weekly outreach crawls—slow, boisterous walks through some of Northeast LA’s densest, most rent-burdened communities. As they walked, the group of 15 to 30 union members played music, posted and distributed LATU flyers, and announced critical updates about Covid-19 tenant protections over a megaphone in English and Spanish. One of these crawls took the group through the largely Latinx and swiftly gentrifying corridor of the 110 Freeway in Highland Park, where NELo members first met a handful of longtime residents of 249 South Avenue 55.

Their stories were horrifying, and all-too common. Less than a year before, in October 2019, their two-story, 40-unit building had been purchased by a new landlord, “Ave 55 19 LLC,” one of the many shell entities used by Alpine LA Properties. [1] At the time of purchase, about 30 of the units were occupied by longtime, predominantly Latinx families, while the remaining 10 units were either empty or had been recently re-rented. An intense campaign to rid the building of its longtime residents began almost at once. Along with DeBoth, a man named Angel Escobar began showing up at the building every day, insisting on speaking to tenants about an “opportunity” to sign “voluntary vacate agreements,” colloquially referred to as cash-for-keys offers. Initially, Escobar and DeBoth tried using salesmanship to convince residents to sign these agreements, but their tactics quickly turned coercive and violent.

“Alpine LA Properties insisted that if a tenant didn’t sign, the sheriff—or they themselves—would show up to forcibly remove the tenant from their home. They threatened direct physical violence. They threatened to call ICE or otherwise use tenants’ immigration status against them.”

They lied to tenants, telling them the building was going to be demolished and that the buyout offers were the tenants’ best and only option. They told tenants that if they didn’t take the small amount of money offered now, they wouldn’t receive any money in the future and would be evicted anyway. They often insisted that if a tenant didn’t sign, the sheriff—or they themselves—would show up to forcibly remove the tenant from their home. They threatened direct physical violence. They threatened to call ICE or otherwise use tenants’ immigration status against them. They almost always presented Spanish-speaking tenants with contracts exclusively in English. Tenants who still refused were often issued “3-Day Notices,” containing false accusations of frivolous lease infractions that made the threat of eviction seem all the more real. Again deploying the weapon of atomization, DeBoth and Escobar pitted the tenants against each other by offering cash bonuses for each additional neighbor they could convince—by any means—to take the offer, effectively inciting violence within the building. Escobar, who boasts on his social media about the sickening strategies he employs to “get the signature,” was particularly vicious, verbally abusing tenants, using bigoted language, banging on their doors or calling at all hours of the day and night.

It should come as no surprise that, by the time members of NELo arrived at the building in the summer of 2020, 20 of the 30 units that had been occupied by longtime residents were empty. The residents—many of them large, multi-generational families—had accepted “voluntary” agreements. The half-empty building felt haunted—gutted units strewn with debris, a leaking swimming pool, walkways overgrown with agave and weeds. Speaking about it, many of the longtime residents who had resisted Alpine LA Properties’ efforts to displace them still seemed stunned by what had occurred. They hadn’t openly and collectively discussed the violence to which they’d been subjected and which, it soon became clear, they were still experiencing. They had held out for months against Escobar and DeBoth’s assault, but some feared that it was only a matter of time before they, too, would be displaced.

[1] For an in-depth analysis of how predatory landlords utilize LLCs as a crucial part of their racist “eviction machines,” see Joel Montano’s dissertation, “Piercing the Corporate Veil of LLC Landlordism: A Predatory Landlord’s Eviction Machine of Black and Brown Bodies in Los Angeles’ Working-Class Neighborhoods, 1996-2019.”

The Unhousing Department: How the city incentivizes and facilitates displacement

It is important to understand that the forced displacement the Ave 55 tenants endured at the hands of Alpine LA Properties is actively facilitated by Los Angeles’ legal system and housing department. The institutions claiming to protect tenants actually function to certify and sanitize the racialized violence of gentrification. They are tools for real estate investors to accumulate capital through dispossession using a process that exists solely to create a veneer of fairness—a veneer that cracks immediately upon even the slightest investigation.

The case of 249 S Ave 55 is an all-too-typical example of how state-sanctioned accumulation through dispossession works. Because it was constructed before 1978, 249 S Ave 55 is covered by the Los Angeles Rent Stabilization Ordinance (RSO), meaning the Ave 55 tenants are afforded certain legal protections. Their rent increases are limited to 3–4% annually—a rate which, though it still outpaces growth in both wages and prices, nevertheless clocks in well below the exorbitant “market-rate” rental increases that accompany gentrification. There is a fairly limited number of reasons a landlord can terminate an RSO tenant’s lease. As in other U.S. cities with rent stabilization protections, RSO units occupied by longtime tenants provide essentially the only truly affordable, stable housing in Los Angeles.

Of course, there is a catch. Not only is the expansion of RSO protections to newer buildings prohibited by the statewide Costa-Hawkins Act of 1995; the same Act also established a crucial loophole in L.A.’s Rent Stabilization Ordinance: the prohibition of “vacancy control.” Any time someone moves out of or is evicted from a rent-stabilized unit in L.A., the stabilized price vanishes and the unit can be placed back on the market at any rate. [2]

“policies and institutions claiming to protect tenants actually incentivize, sanitize, and legitimize profit-making via dispossession.”

The vacancy decontrol loophole is no mere oversight in rent stabilization policy. It is a foundational feature that makes rent stabilization in its current form palatable to speculative real estate interests, and it’s precisely the reason Alpine LA Properties purchased 249 S Ave 55. [3] When Alpine LA Properties bought the property in the fall of 2019, the majority of the predominantly Latinx tenants were paying far below the neighborhood’s market rate. This comparatively low monthly yield is why Alpine LA Properties would pay $10,600,106 for the building—far too high a price if we consider only the revenue the building was bringing in at the time of the purchase, but a steal considering the building’s market-rate earning potential. Alpine LA Properties’ acquisition only makes financial sense when viewed as an investment opportunity to immediately and substantially raise rental revenues by removing the 30 longtime tenants and replacing them with richer—and almost certainly whiter—tenants who could be charged the going rate in Highland Park ($2,000/month for a one-bedroom).

What’s more, the current system of rent stabilization also provides the legal mechanism by which a company like Alpine LA Properties can swiftly dispossess tenants who are supposedly protected by the RSO: the “voluntary vacate agreement.” L.A.’s Housing and Community Investment Department (HCID) permits landlords to make buyout offers to RSO tenants by setting minimum (and utterly insufficient) buyout amounts—amounts that landlords can hold up as the city-authorized price of a unit. While HCID is ostensibly charged with communicating to tenants that they have the absolute right to refuse these offers, that almost never happens in a way that’s effective.

For longtime residents paying affordable rent far below the market rate, being coerced into accepting a “voluntary vacate agreement” is a catastrophic, sometimes deadly event. The buyout amounts are never enough for residents to sustainably and safely stay in their communities or, for many, to stay housed at all. That’s why the offers are nearly always accompanied by the kind of coercion and harassment the Ave 55 tenants suffered. In fact, the need for henchmen like Escobar and DeBoth to take on the legally murky, cynical job of coercing tenants into giving up their homes has created a lucrative cottage industry in Los Angeles referred to as “re-tenanting.” A cadre of paid young “professionals,” hungry to move up the corporate ladder, have developed the coercive and violent tactics needed to pressure families to leave their homes of 20, 30, 40 years. HCID and the city understand all this. Yet they pretend that tenants across L.A. accept such buyout offers of their own free will—and even worse, that the offers constitute a “fair” economic practice. [4]

In this way, the policies and institutions claiming to protect tenants actually incentivize, sanitize, and legitimize profit-making via dispossession. [5] After many long months of direct appeals to local politicians and concerted campaigns to work through HCID, all of which yielded few results, the Ave 55 tenants developed an understanding that, in their struggle to defend their homes, the institutions of the state weren’t simply neutral. These institutions were active, collaborating partners in the tenants’ displacement.

[2] The other key loophole in the Los Angeles RSO is the Ellis Act, passed in 1985 as the first state-wide reaction to the rent control movement of the late 1970s. From the L.A. Tenants Union website: “The Ellis Act is a California state law that allows landlords to evict tenants in rent-controlled units if they are planning to ‘go out of business.’ The public excuse for the law was that it would protect small ‘mom and pop’ landlords who wanted to retire. In actual practice, it is used almost exclusively by corporate landlords and developers to flip buildings and tenants out of rent stabilization. [Landlords] then either demolish the buildings, convert them into condos or boutique hotels, or list vacated units on Airbnb illegally.” To get a sense of the scale of the devastation that the Ellis Act has wrought in Los Angeles, see the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project’s powerful visual representation of all 27,243 (and counting) Ellis Act evictions since 2001.

[3] Both Prop 10 (2018) and Prop 21 (2020) would have repealed the Costa-Hawkins Act and therefore allowed municipalities in California to introduce (or reintroduce, as in the case of Berkeley, Santa Monica, West Hollywood, East Palo Alto, Cotati, and Palm Springs) vacancy control. Both Propositions were defeated soundly, in no small part because of the massive amounts of money the real estate industry (and especially Wall Street landlords like Blackstone Group, Essex Property Trust, and Equity Residential) poured into their defeat. Here is a list of the top 10 contributors to the anti-Prop 10 campaign. And here is a dated but still extraordinarily useful history of rent control struggles in California (and the parallel struggles happening in Massachusetts).

[4] The L.A. Tenants Union produced a “buyout calculator” in 2018 in order to demonstrate just how raw a deal cash-for-keys offers really are. Even if we ignore moving costs and higher income taxes as a result of accepted buyouts, the HCID-sanctioned amounts will be gone in less than two years for the majority of longtime, low-income tenants in Los Angeles.

[5] For a similar argument about the way “Affordable Housing” policy in fact facilitates real estate capital accumulation, see Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal’s “The Enduring Fiction of Affordable Housing.”

Hell on earth: Alpine LA Properties’ Campaigns of terror during illegal construction

In the weeks that followed the first meeting with the Ave 55 tenants, NELo members quickly realized that the landlord’s effort to displace the longtime tenants hadn’t ended with the initial wave of cash-for-keys harassment. A second round of horror had commenced, in many ways more violent than the first. Shortly after Alpine LA Properties expelled two thirds of the longtime families, the company began conducting illegal, unpermitted construction on the recently emptied units. While Alpine LA Properties obviously wanted to refurbish the vacated units as cheaply and superficially as possible in order to flip and re-rent them at higher rates, the illegal construction was also clearly intended to target and terrorize the remaining tenants who had not yet “voluntarily agreed” to leave.

Rather than simply renovating individual units, the landlord’s unpermitted construction crew trashed the building, piling hazardous waste in public spaces and likely releasing toxic chemicals—including lead and asbestos—into the air. Workers conspicuously ran power tools outside longtime tenants’ units for hours at a time for no discernible reason. On three separate occasions, they smashed basketball-sized holes through the bathroom ceilings of first-floor tenants and waited weeks before patching and cleaning. In perhaps the single most violent case, the crew demolished a longtime Latinx family’s bathroom, supposedly to fix a leaking pipe, then refused to patch the walls for months, leaving the room so exposed to the elements that swarms of roaches and families of rats invaded the apartment.

The message was unambiguous: If you haven’t yet accepted a “voluntary” agreement to vacate, we are going to make your home hell on earth until you do. Management wasn’t guarded about their intentions. When one of the newer, white, gentrifying couples called the landlord to complain about the cockroaches entering their unit during construction, the maintenance officer said, “Which unit are you in, again? Oh, right, you’re one of the ones we want to keep.” When the Latinx tenant whose bathroom was destroyed repeatedly complained that repairs were taking far too long, Angel Escobar returned to tell her that the repairs were not a priority, and that she could move out if she wanted to keep her family safe and healthy.

“The message was unambiguous: If you haven’t yet accepted a ‘voluntary’ agreement to vacate, we are going to make your home hell on earth until you do.”

The Tenants Association: From Crisis to communal power

When the Ave 55 tenants formed their tenants association (TA), these were the issues they came together to confront. Along with members of NELo, they created a building-wide, bilingual text thread and began holding weekly bilingual meetings in their courtyard, sharing their stories, learning about one another’s lives and experiences, and strategizing together about how to address their habitability concerns and Alpine LA Properties’ continued harassment. The TA’s concrete successes were immediate:

Within weeks, they learned how to navigate the city’s convoluted bureaucracy for filing complaints, exploiting it for their own purposes in order to delay and complicate Alpine LA Properties’ illegal construction.

When Escobar and DeBoth threatened a longtime disabled Latinx tenant with illegal eviction, TA members used the text thread to organize a 24/7 eviction watch that culminated in a successful confrontation; Alpine LA Properties’ agents were turned away by a group of tenants who physically blockaded their neighbor’s door.

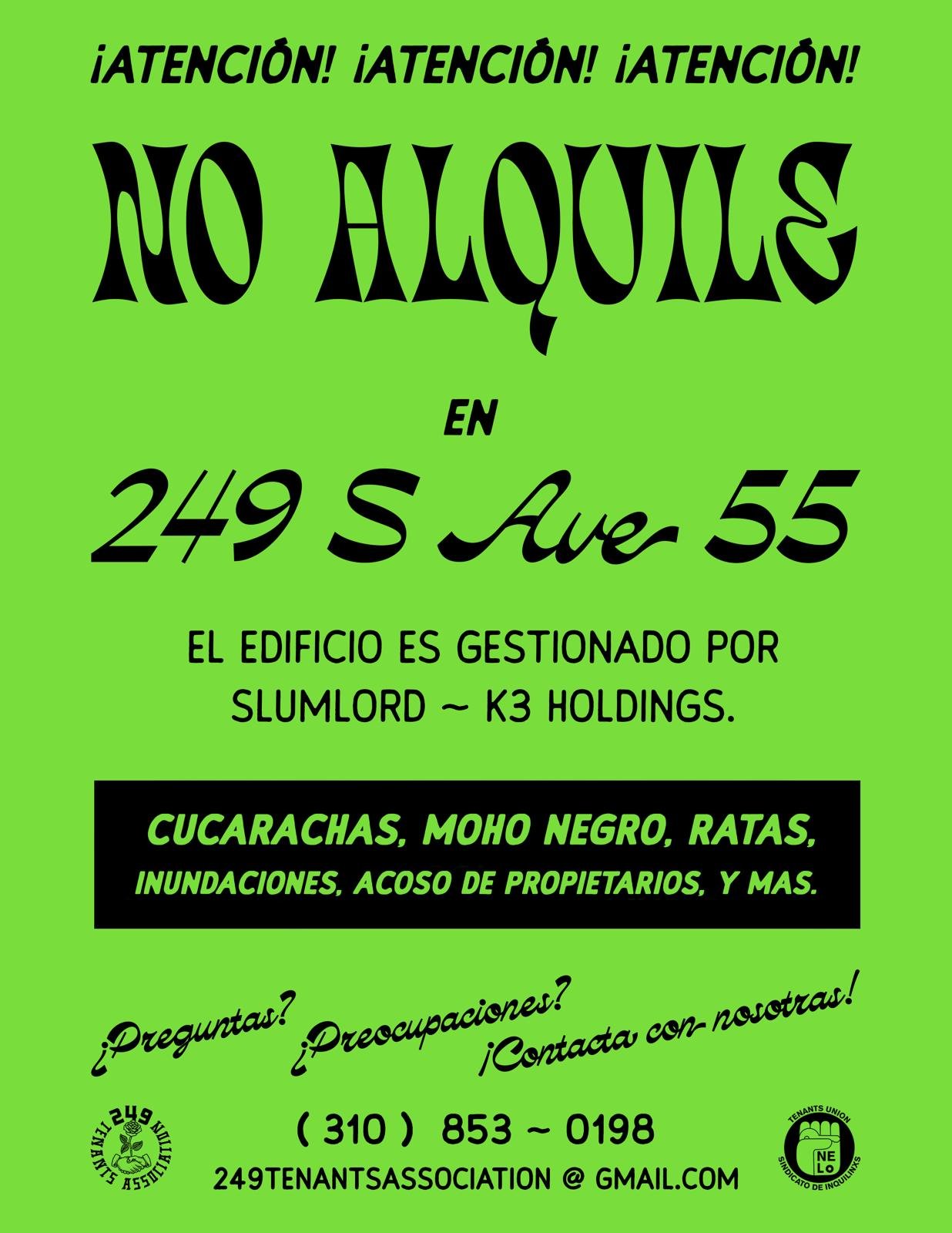

The tenants posted “Protected by LATU” and “Do Not Rent Here” signs in their windows, visually communicating their unity, and began collectively confronting prospective renters who visited the property. By explaining Alpine LA Properties’ practices and the conditions in the building to prospective tenants, often in front of a sputtering, incensed Alpine LA Properties leasing agent, the association managed to keep most of the renovated units unoccupied for many months.

These creative organizing strategies applied material pressure to Alpine LA Properties and forced it to yield to the tenants’ demands. By March 2020, the Ave 55 tenants organized an outreach crawl of their own, posting signs outside their building and across the neighborhood, announcing their presence and offering solidarity and support to their neighbors.

The Ave 55 TA has forged an uncommon community between a group of mostly young, multiracial gentrifying tenants and their Latinx neighbors who have resided in the building for decades. Shared habitability crises brought tenants from different backgrounds together. But, only through building genuine friendship with their working-class, Latinx neighbors did the gentrifying tenants begin to understand both their complicity in the violence of gentrification and their collective interest in ending that violence. After all, the violence of gentrification and the interests of real estate capital depend on the assumption that gentrifying tenants—most of whom are rent-burdened, debt-burdened, and effectively working-class, even if they are encouraged to imagine themselves otherwise—will never recognize their shared interests and build solidarity with longtime tenants, unhoused tenants, and other dispossessed and migrant groups. In this sense, some of the most radical activities developed by the Ave 55 TA may be the seemingly mundane ones—the small communal habits that have begun to forge lasting relationships across class and race.

In the midst of this powerful building-level organizing, the Ave 55 TA and their partners in NELo made an important discovery: Alpine LA Properties owned twenty other properties across Los Angeles. Just like 249 S Ave 55, the majority of these properties were RSO buildings in gentrifying neighborhoods that had been purchased in the previous year.

The stakes of displacement: gentrification as social cleansing

It has often been observed that—with an ironic logic full of radical potential—specific forms of exploitation and oppression create the conditions for specific forms of transformational struggle. In the case of Alpine LA Properties and the practice of real estate speculation more generally, the targeted acquisition of similar buildings across Los Angeles planted the seed of mass, cross-building solidarity, though this seed required (and requires) intentional, organizational nourishment in order to flourish.

Michael & Nathan Kadisha

After a little digging, the Ave 55 tenants and their partners in NELo found that behind Alpine LA Properties were twin brothers in their 20s, Michael and Nathan Kadisha, and a third young Kadisha named Joshua. Through their relationship to the telecommunications magnate and billionaire investor Neil Kadisha, Michael and Nathan are the inheritors of a vast fortune now largely invested in real estate. The Kadisha family also owns Omninet Capital, which controls over $1 billion in commercial real estate assets and 13,000 residential units around the country. Their empire likely extends even further: the Kadishas are connected by marriage to the wealthy Nazarian family, well-known investors, “philanthropists,” and businesspeople with similarly extensive holdings.

“The stakes of displacement are life and death.”

Alpine LA Properties made its first L.A. purchase in 2016—a 4-story, 32-unit building with a brick facade in a gentrifying part of Koreatown. Eight months later, the company acquired a second property, a 4-unit complex in gentrifying Boyle Heights. Then three more properties in Boyle Heights. Then another two in Koreatown. Then a building in Highland Park. Another in Koreatown. Two more in Highland Park. Another buying frenzy as the COVID-19 pandemic ravaged working-class neighborhoods: ten buildings in Koreatown, which brought their L.A. portfolio to at least 21 properties (that we know of).

Since descending on Los Angeles in 2016, the Kadisha brothers, fresh out of college, have invested over $120 million into residential real estate. It’s important to appreciate the full scale—and the brutal, racist logic—of the devastation that Alpine LA Properties and the Kadisha brothers have wrought on the communities where they purchased buildings.

A partial portrait of this devastation emerges when we examine HCID’s publicly available records of the “voluntary vacate agreements” made at Alpine LA Properties’ properties. Although HCID only records “agreements” that were officially filed with the city and thus doesn’t include Alpine LA Properties’ many illegal, unreported buyout offers and other illegal evictions—including “self-evictions” achieved through lack of repairs, harassment, and exploitation of tenants’ increased precarity during the pandemic—the numbers remain overwhelming. From HCID’s official records:

3048 West 12th Street: between October 2019 and January 2020, 9 buyouts

437 North Ardmore Avenue: between December 2019 and May 2020, 58 buyouts

249 South Avenue 55: between July 2019 and March 2020, 20 buyouts

941 South Kenmore Avenue: between November 2020 and January 2021, 7 buyouts

915 South Kenmore Avenue: between November 2020 and January 2021, 4 buyouts

200 South Kenmore Avenue: between November 2020 and January 2021, 12 buyouts

410-414 South Manhattan Place: between June 2020 and January 2021, 15 buyouts

727 South Mariposa Avenue: between October 2020 and November 2020, 29 buyouts

975-985 South Oxford Avenue: between December 2019 and January 2020, 8 buyouts

207 North Oxford Avenue: between May 2020 and August 2020, 4 buyouts

Between July 2019 and January 2021—through the catastrophic spike of COVID-19—Alpine LA Properties displaced tenants from 166 units using “legal” cash-for-keys buyouts. If we assume an average household of 2.8 people—though the household size was likely higher, given the ways poor people are forced to share limited space in order to survive—Alpine LA Properties violently displaced about 465 people in a year and a half, intentionally using the distress brought by the COVID-19 pandemic to accelerate their efforts. Like the tenants at 249 S Ave 55, the vast majority of these people are Latinx, many are undocumented, and many had lost work, lost income, or battled illness themselves. This is the Kadisha brothers’ business model, one that is all too common in L.A: systematically identify “underperforming” RSO buildings and then cleanse those buildings of poor, predominantly Latinx families in order to re-rent the emptied units for a massive profit.

“For Alpine LA Properties to make money, low-income families have to be torn from the webs of survival and livelihood they have spent lifetimes, even generations constructing.”

This practice can only be described as social cleansing. In the popular imagination, the terms “social cleansing” and “genocide” are associated with images of mass graves, whereas the term “gentrification” merely calls to mind hipster coffee shops, overpriced lattes, renovated facades. Indeed, real estate agents use the term “gentrification” almost gleefully, as a selling point. But it is crucial to understand that genocide and gentrification are, in fact, inseparable.

For Alpine LA Properties to make money, children have to be torn from their schools and their networks of friends. Low-income parents have to be torn from the webs of survival and livelihood they spent lifetimes, or even generations constructing—jobs, healthcare services, extended families, churches, childcare circles, social clubs, communities. In the final analysis, people have to die for Alpine LA Properties to make money.

A fraction of the (at least) 166 families displaced by Alpine LA Properties may have managed to find smaller, more expensive apartments nearby, apartments from which they’ll be displaced again in the near future when their cash-for-keys money runs out, or for which they’ll have to make huge sacrifices in order to afford. Many others, in all likelihood, simply left the city, following the hundreds of thousands of poor Black and Latinx people who have been expelled from Los Angeles in the past few decades, pushed to the Inland Empire, desert cities, and other states: Arizona, Nevada, Texas.

We know that at least one family displaced from 249 S Ave 55 is now unhoused, living in their vehicle at a campground. Another former Ave 55 resident has spent over a year searching in vain for stable, affordable housing in the neighborhood and continues to sleep on the floors of friends’ apartments. One elderly Latinx woman from Ave 55—a woman who was convinced by Escobar and DeBoth that her eviction was inevitable so she might as well take the meager sum of money and relocate—became ill during the physical and emotional stress of moving, and died.

There is nothing figurative, then, in the repeated claim of tenant organizers that “eviction is death.” Whether we mean corporeal death or social death—that is, the destruction of those modes of sociality that allow us to reproduce our lives and to live meaningfully—the stakes of displacement are just that: life and death. Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s definition of racism is “the state-sanctioned and/or extralegal production and exploitation of group differentiated vulnerabilities to premature (social, civil and/or corporeal) death.” Joy James insists that talking about racism is “virtually meaningless when severed from genocide.” Following the official United Nations definitions of the terms, targeted, systemic displacement—i.e., “gentrification”—constitutes social cleansing and genocide. We need only think of the four unhoused people who die every day in Los Angeles, many of whom are longtime residents of the city displaced by gentrification, and who are disproportionately Black and indigenous. Even if there are no mass graves, even if the violence is not spectacular enough, too quotidian, too mundane and methodical—too legal—to ever be named as such in popular discourse, the genocide of the poor is ongoing today in every urban center in America.

In 249 S Ave 55, where there was once a community of Latinx tenants—poor and struggling, to be sure, but nevertheless surviving and contributing to the survival of their neighborhood—there is now an absence, a scar, a record of violence. It’s no coincidence that many of those displaced by Alpine LA Properties are indigenous people from rural regions of Latin America, and it’s no exaggeration to say that Alpine LA Properties’ “business model” repeats the logic of the original, genocidal violence and dispossession used against the indigenous inhabitants of what is now Los Angeles, a logic that created and continues to underwrite all real estate capital and private property in the United States.

Brick by Brick: Leveraging the L.a. tenants union to form the k3 council (Alpine LA Properties)

When the Ave 55 TA and their LATU Northeast Local partners understood that 249 S Ave 55 was not alone, they realized two things:

their own organizing and demands would be stronger with the support of other buildings, and

people in the other buildings likely needed the Ave 55 tenants as much as the Ave 55 tenants needed them.

The need for a K3 Tenant Council—a group of tenant associations in many different buildings owned by Alpine LA Properties—thus emerged as a direct response to their landlord’s violent practices. Although Alpine LA Properties had already succeeded in displacing hundreds of people from their buildings, many of the tenants who had refused initial cash-for-keys offers at Alpine LA Properties’ other properties were ready to organize and fight to defend their homes.

The larger structure of the L.A. Tenants Union was essential to supporting these tenants from across the city. The process started in November 2020, when a group of LATU members from four different locals—the Northeast Local, Vermont and Beverly (VyBe), Mid-City, and Eastside Unión de Vecinos—committed to helping all tenants in Alpine LA Properties buildings form tenants associations. Using targeted multi-lingual flyers, the LATU members went door to door at the other Alpine LA Properties buildings, where they found tenants who largely shared the experiences of the tenants at Ave 55. These tenants, too, told stories of lies and harassment, threats of ICE and “lost” rent checks, fabricated lease violations and verbal and physical abuse. And though not all the buildings were willing to organize—some of them, such as 437 North Ardmore Avenue, where Escobar serves as the building manager, had been so decimated by Alpine LA Properties’s tactics that there were few longtime tenants left—many of them were. By the middle of December, 10 of the buildings had formed tenants associations and had sent letters to Alpine LA Properties declaring their solidarity with the tenants in Alpine LA Properties’ other properties.

On the surface, the principle of a tenants association is straightforward. Against the atomization of the individual rental contract, which alienates and divides tenants from one another and thereby gives landlords power over them, a TA makes a simple yet radical claim: as tenants, we do not live in our buildings or on our blocks alone. Instead, we live in community, intimately bound to our neighbors (whether we like them or not) and utterly dependent on them as the co-creators of the spaces—the buildings and courtyards and blocks and parks—where we live out and reproduce our lives. A tenants association therefore doesn’t exist solely to address a shared crisis, such as cash-for-keys harassment from a landlord like Alpine LA Properties. Instead, it might be more accurate and generative to think of TAs not only as instruments of community defense—against landlord harassment and landlord negligence, against rent increases and evictions—but also as ends in themselves, ways of being together and sharing space together that deepen, enrich, and create meaning in our social lives. The Ave 55 tenants, for example, have used the foundation of their weekly TA meetings to strengthen the bonds and expand the practices of mutual care that already existed in the building. They now communicate about everything, resolve common quarrels among neighbors, hold mail for one another, share groceries and simple household items, run errands and cook for neighbors who are busy or sick, maintain an herb garden together in a reclaimed corner of their building’s lot, host picnics and breakfasts for the building, and celebrate birthdays together.

“this coming together was neither inevitable nor easy. It involved work—lots of work—and the development and practice of our capacities for trust and care.”

Of course, these two functions of TAs—the TA as a means of collective defense against the landlord and the TA as a form of sociality as an end in itself—are inseparable in practice. The Alpine LA Properties tenants associations are a perfect example of this. The spark for these TAs was the recognition among the tenants that they shared a condition of duress, and the immediate further recognition that they stood a much better chance of withstanding this duress if they joined together in mutual support. But this coming together was neither inevitable nor easy. It involved work—lots of work—and the development and practice of the tenants’ capacities for trust and care. For instance, it involved tenants with longstanding feuds with one another, or tenants who hadn’t spoken to one another in years, trusting one another enough to share intimate, personal information. And it involved tenants doing that most difficult thing—asking for help—and having the humility and grace to accept that help when it was offered.

Building and sustaining a tenants association is a never-ending process; it requires constant renewal. It requires learning—or perhaps relearning—the concrete rituals of community that so many of us are unaccustomed to practicing. Forming strong new bonds that cross ethnic, linguistic, generational, cultural, and class lines, TAs become spaces of communal transformation. This transformation, this practice and expansion of the habit of communal care, is what makes TAs more than instruments to achieve some external goal. TAs can allow us to reproduce our lives in different, richer, more meaningful ways. TAs are both the path and the goal toward which we’re moving.

The Alpine LA Properties tenants associations won swift and remarkable victories. In the buildings where cash-for-keys harassment was ongoing, the tenants—by creating militant rapid response networks, threatening legal action, and replacing individualized communication with Alpine LA Properties with collective communication through TA-wide emails accounts—forced Alpine LA Properties to stop making these offers altogether. In fact, Escobar now refuses to step foot in several of the buildings, for fear of how the TAs will mobilize a collective confrontation. TAs also forced Alpine LA Properties to begin repairs that had long been ignored: mold was removed, plumbing was repaired, tubs were re-caulked, broken screens were replaced. All their demands were collectivized, so that Alpine LA Properties could no longer treat long-standing tenants differently from the newer, gentrifying tenants in the buildings.

“The council forced Alpine LA Properties to begin repairs that had long been ignored: mold was removed, plumbing was repaired, tubs were re-caulked, broken screens were replaced.”

Clearly, a major reason for these victories was that the buildings were no longer struggling in isolation. Alpine LA Properties began to recognize that the cross-building organizing could lead to a large, multi-building lawsuit. And, most importantly, the TAs themselves began to realize what it meant to have tenants across the city struggling alongside them. Suddenly, every action that an individual TA took contained within it the actions that all the other TAs had taken before as well as the potential actions they might take together in the future. The TAs reflected back their power to one another—informing each other of victories, encouraging each other not to back down, asking each other for support—and this process of mutual reflection created a sort of amplification, building the TAs’ confidence, opening up possibilities for even bolder actions and demands. Certainly, the Ave 55 tenants would not have confronted DeBoth as militantly as they did on that December afternoon if they hadn’t first witnessed a similar show of force at another Alpine LA Properties building in Highland Park months prior. In turn, the Ave 55 tenants’ militancy had a rippling effect: only a week after the confrontation about the toxic carpet, a tenant in an entirely different Alpine LA Properties building received the repairs for which she had been asking for over a year. The trust, solidarity, and collective action within individual TAs had started to spread between buildings, creating new bonds and relationships—a new community of tenants—that hadn’t existed before.

A Movement for Life: Relearning and renewing our habits of assembly

Beginning in early 2021, the various Alpine LA Properties tenants associations have started to gather for monthly meetings of the K3 Tenant Council. The process of creating this Council—the first such Council in LATU’s six-year history, though other autonomous tenants unions (such as TANC, Tenant and Neighborhood Councils in the Bay Area) have been working with similar organizational forms for some time—has been full of trials and experimentation. Perhaps the primary challenge has been a variation on the same challenge that confronts all our efforts to “relearn and renew our habits of assembly,” as Manolo Callahan puts it. Even after months of Council-wide meetings, each of which has been attended by 40-50 tenants from the different Alpine LA Properties buildings, a sense of true cross-building solidarity remains fleeting. Only for brief, vibrant flashes—during spontaneous chants at the two Council-wide marches, for instance, or during moments of intense sharing and care in the Council-wide meetings—has the Council felt like a genuine community: a true collective committed to making decisions together, acting together, taking risks together.

“Assembling is both an instrument of defense and that which is being defended, and these two practices of assembly mutually strengthen and advance each other.”

With vaccinations widely available in Los Angeles, the Council has decided to shift its monthly meetings from the flattening, atomizing space of Zoom to in-person picnics in local parks. The first picnic was almost entirely “social,” an opportunity for tenants from the different buildings to come together to eat tacos and pupusas and talk. Toward the end of the gathering, before the cake was served, the tenants spent an hour or so in a wide circle on the grass, sharing stories as a group, discussing possible next steps that they might take as a Council (such as creating a list of Council-wide demands). More than anything, the gathering created space for the tenants to start getting to know one another more deeply, to start learning one another’s histories, interests, and struggles. In this way, the picnic was a celebration, an opportunity to accept and enjoy the peculiar, ironic gift that Alpine LA Properties had given these tenants: bringing them together in a way that had the potential to transform them from atomized victims of their landlord into more human human beings (as Grace Lee Boggs might have put it).

This kind of celebratory sociality is political. The Alpine LA Properties Tenant Council gathered in order to resist and defend their homes against their landlord. But they are resisting and defending their homes precisely in order to be able to gather under more liberated, less oppressive conditions. Assembling is both an instrument of defense and that which is being defended, and these two practices of assembly mutually strengthen and advance each other.

What else might these practices of assembly make possible? As tenants in struggle, we do not necessarily want to set a goal in the abstract, but rather “act our way into thinking,” as Leonardo Vilchis, a member of the Unión de Vecinos Eastside Local of LATU, often says. Yet discussions have started in some of the Alpine LA Properties tenants associations that indicate possible directions. For instance, building on the success of their previous collective actions, members of the Ave 55 TA have started to wonder about the possibility of a collective bargaining agreement with their landlord: a process of negotiating a collective rental contract (similar to the collective contracts negotiated by labor unions) which, through the threat of a building-wide rent strike, would force Alpine LA Properties to lower everyone’s rent. Of course, the bargaining position of the Ave 55 TA would be exponentially stronger if their “bargaining unit” included the members of the other Alpine LA Properties TAs as well, but such cross-building solidarity will require the continued cultivation and growth of these relationships.

Perhaps even more importantly, the Ave 55 tenants and a few other Alpine LA Properties TAs have also started to see their building-level organizing as inseparable from the defense of their immediate neighborhoods. These TAs have begun to use some of their meetings to do outreach to their surrounding blocks, creating flyers that share their building’s story and encourage tenant neighbors to attend a TA meeting to receive support, learn, or simply build community. In this way, too, the TAs are beginning to see themselves not just as antagonists against Alpine LA Properties, but rather as neighborhood-level nodes of community defense, spaces in which new, potentially transformative social relations can be built.

Other radical possibilities exist. The Alpine LA Properties tenants could look to the Hillside Villa Tenants Association in L.A.’s Chinatown for guidance. Also supported by the L.A. Tenants Union as well as Chinatown Community for Equitable Development (CCED), the Hillside tenants have made a militant demand of the L.A. City Council: use Eminent Domain to purchase their building from their speculator-landlord, Tom Botz, who has attempted (both before and during the pandemic) to evict tenants and double or even triple the rents. The simplest, best way to create and preserve truly affordable housing, the Hillside tenants argue, is to expropriate that housing from price-gouging landlords, making the housing public and turning over control to the organized tenants who live there.

There is much work to be done. But one lesson from the ongoing struggle of the Alpine LA Properties tenants is that this work—this sharpening of the weapon of solidarity—must also be a celebration. Another oft-repeated phrase of L.A.’s tenant unionists is that “we make our community by defending it.” The Alpine LA Properties tenants have helped to teach us that the opposite is true as well. We defend our communities by making them. Our movement is not just a movement for housing, but a movement for life.

Resistencia a la limpieza social en Los Ángeles: los orígenes del Consejo de Inquilinos K3 (Alpine LA Properties)

Si se le pidiera a los inquilinxs del 249 de la Avenida Sur 55 que identificaran cuándo descubrieron por primera vez su poder colectivo, tal vez indicarían una tarde a finales de diciembre de 2020, justo cuando Los Ángeles se convertía en el epicentro mundial de la pandemia del COVID-19.

Matt DeBoth, un administrador de bajo rango de propiedades para su arrendador—la empresa de inversiones inmobiliarias Alpine LA Properties, con sede en Los Ángeles—tenía que reunirse con una residente del edificio desde hacía mucho tiempo para hablar sobre el moho que se había acumulado en su alfombra durante más de una década. La inquilina, una madre latina e hispanohablante, llevaba más de 20 años viviendo en el edificio. Probablemente, DeBoth supuso que la interacción se desarrollaría de la misma manera que en el pasado: la inquilina lidiaría con la barrera del idioma, intentando demostrar la gravedad de la situación, y DeBoth minimizaría el problema, enmarcando cualquier trabajo de mantenimiento superficial que permitiera como un regalo raro y benévolo. El mensaje implícito era siempre claro: Alpine LA Properties se alegraba en mantener condiciones peligrosas e inhabitables en su casa con la esperanza de que ella y su familia se auto-desaloje. En todas sus interacciones con los antiguos residentes del 249 de la Avenida Sur 55, DeBoth desplegó de forma rutinaria el arma favorita de todos los arrendadores: aislamiento y atomización.

“Alpine LA Properties se alegraba en mantener condiciones peligrosas e inhabitables en su casa con la esperanza de que ella y su familia se auto-desaloje.”

Sin embargo, en lugar de reunirse con un solo inquilino aislado aquella tarde de diciembre, DeBoth se encontró con algo muy diferente. Cuando dio un paso en el patio al aire libre del edificio de dos plantas, se encontró con una docena de inquilinxs -residentes latinxs de ataño junto a jóvenes blancos, afro-descendientes y asiáticos gentrificadores- enmascarados, con los brazos cruzados, formados en un semicírculo amplio

Se retiraría la antigua alfombra y se instalaría una nueva, le informaron a DeBoth. Hoy.

DeBoth hizo todo lo posible por mantener la ventaja, tratando con condescendencia a los inquilinxs y "explicándoles"—en el tono casi patológicamente optimista que utiliza incluso cuando amenaza a la gente con el desalojo—que no era necesario cambiar la alfombra. Repitió esta frase incluso después de que los trabajadores de mantenimiento empezaran a levantar la alfombra, revelando grandes franjas de moho negro tóxico y extensos daños causados por la humedad que se ha filtrado durante años a través de los cimientos. Un problema menor, insistió DeBoth. La alfombra vieja y mohosa podía limpiarse ligeramente y volver a instalarse, sin necesidad de una nueva.

Mientras que en el pasado esta estrategia había tenido éxito contra inquilinxs individuales, fracasó contra el poder colectivo de todo un edificio. Rodeando a DeBoth, grabando cada momento de interacción, los inquilinxs del Ave 55 se mantuvieron firmes en su simple demanda. Los trabajadores de mantenimiento parecieron comprender intuitivamente que la dinámica de poder había cambiado; sin esperar la aprobación de DeBoth, quitaron la alfombra y la llevaron al contenedor de basura. Atemorizado, DeBoth dio un giro y habló vagamente de un "precio justo" por su sustitución. Pero la escritura estaba en la pared: Alpine LA Properties pagaría la sustitución de la alfombra. Los inquilinxs, unidos en apoyo de su vecino, habían ganado. Y no habían ganado mediante la intervención del departamento de vivienda, ni de un funcionario electo, ni de un abogado, opciones que ya habían agotado, con pocos resultados. Lograron esta pequeña pero significativa victoria utilizando el arma de la solidaridad organizada y la confrontación directa, haciendo valer colectivamente lo que necesitaban y luego tomándolo.

Al final de la interacción, aferrándose a su posición de autoridad, DeBoth tuvo el descaro de sugerir que la inquilina debería considerar su nueva alfombra "un regalo de Navidad anticipado de Alpine LA Properties". Ella y sus vecinos se rieron de él en la puerta principal.

Las semillas de la solidaridad: conocer a los vecinxs, el reconocimiento de la violencia a la que nos enfrentamos

Los inquilinxs del 249 de la Avenida Sur 55, con el apoyo de los miembros de la Seccion Noreste del Sindicato de Inquilinxs de Los Ángeles, se han organizado como Asociación de Inquilinxs del 249 de la Avenida Sur 55. No siempre tuvieron el tipo de solidaridad que mostraron aquella tarde de diciembre. La historia de cómo construyeron (y siguen construyendo) ese poder, y cómo ese poder contribuye y depende del movimiento más amplio de poder de los inquilinxs en Los Ángeles, tiene mucho que enseñarnos - tanto sobre:

Las formas de organización autónoma y la lucha militante que los inquilinxs en L.A. están construyendo en la lucha contra el capitalismo inmobiliario racial y la violenta limpieza social conocida como "gentrificación"

Los horizontes del movimiento de poder de los inquilinxs, las nuevas relaciones sociales y formas de solidaridad que apuntan a formas más liberadoras, festivas y comunitarias de estar juntos y reproducir nuestras vidas.

Lxs miembrxs de la sección Noreste de SILA (NELo por sus siglas en ingles) conocieron a los inquilinxs de Ave 55 gracias a una práctica comunitaria desarrollada en el verano de 2020, a raíz de los levantamientos de George Floyd. Los miembros de NELo empezaron a llevar a cabo rondas semanales de divulgación: caminatas lentas y bulliciosas por algunas de las comunidades más densas y con mayor carga de alquiler del noreste de Los Ángeles. Mientras caminaban, el grupo de 15 a 30 miembros del sindicato ponía música, colgaba y distribuía folletos de la SILA y anunciaba por megáfono, en inglés y español, informes críticos sobre las protecciones de los inquilinxs de Covid-19. Uno de estos recorridos llevó al grupo a través del corredor de la 110 Freeway en Highland Park, que es mayoritariamente latino y se está gentrificado rápidamente, y donde los miembros de NELo conocieron por primera vez a un grupo de residentes antiguos del 249 de South Avenue 55.

Sus historias eran espeluznantes, y demasiado comunes. Menos de un año antes, en octubre de 2019, su edificio de dos pisos y 40 unidades había sido comprado por un nuevo propietario, "Ave 55 19 LLC", una de las muchas entidades ficticias utilizadas por Alpine LA Properties. [1] En el momento de la compra, alrededor de 30 de las unidades estaban ocupadas por familias residentes de largo plazo, predominantemente latinas, mientras que las 10 unidades restantes estaban vacías o habían sido re-alquiladas recientemente. Casi de inmediato se inició una intensa campaña para deshacerse de los antiguos residentes del edificio. Junto con DeBoth, un hombre llamado Ángel Escobar comenzó a presentarse en el edificio todos los días, insistiendo en hablar con los inquilinxs sobre una "oportunidad" para firmar "acuerdos de desalojo voluntario", coloquialmente conocidos como ofertas de dinero por llaves. Al principio, Escobar y DeBoth trataron de convencer a los residentes de que firmaran estos acuerdos mediante técnicas de vendedores, pero sus tácticas se volvieron rápidamente coercitivas y violentas.

“Alpine LA Properties insistió en que si un inquilino no firmaba, el sheriff -o ellos mismos- se presentarían para sacar al inquilino de su casa por la fuerza. Amenazaron con violencia física directa. Amenazaron con llamar al ICE o con utilizar la condición de inmigrante de los inquilinxs en su contra.”

Mintieron a los inquilinxs, diciéndoles que el edificio iba a ser demolido y que las ofertas de compra eran la mejor y única opción para los inquilinxs. Les decían que si no aceptaban la pequeña cantidad de dinero que se les ofrecía ahora, no recibirían ningún dinero en el futuro y serían desalojados de todos modos. A menudo insistían en que si un inquilino no firmaba, el sheriff -o ellos mismos- se presentarían para sacarlo por la fuerza de su hogar. Amenazaron con violencia física directa. Amenazaron con llamar a ICE o con utilizar la condición de inmigrante de los inquilinxs en su contra. Casi siempre presentaban a los inquilinxs de habla hispana contratos exclusivamente en inglés. A los inquilinxs que seguían negándose se les emitían a menudo "avisos de 3 días", que contenían acusaciones falsas de infracciones frívolas del contrato de alquiler que hacían que el espectro del desalojo pareciera aún más inminente. Una vez más, DeBoth y Escobar desplegaron el arma de la atomización, enfrentando a los inquilinxs entre sí al ofrecerles bonos en efectivo por cada vecino adicional que pudieran convencer, por cualquier medio, de aceptar la oferta, incitando efectivamente a la violencia dentro de los edificios. Escobar, que se jacta en sus redes sociales de las enfermizas estrategias que emplea para "conseguir la firma", se ensañó especialmente, insultando a los inquilinxs, utilizando un lenguaje intolerante, golpeando sus puertas o llamando a todas horas del día y de la noche.

No debería sorprender que, cuando los miembros de NELo llegaron al edificio en el verano de 2020, 20 de las 30 unidades que habían sido ocupadas por residentes de largo plazo estaban vacías. Los residentes—muchos de ellxs grandes familias multigeneracionales—habían aceptado los acuerdos "voluntarios". El edificio semivacío parecía embrujado: unidades desparramadas por los escombros, una piscina con fugas, pasillos cubiertos de agave y hierbas. Al hablar de ello, muchos de los residentes de largo plazo que se habían resistido a los esfuerzos de Alpine LA Properties por desplazarlos parecían todavía aturdidos por lo ocurrido. No habían discutido abierta y colectivamente la violencia a la que habían sido sometidos y que, pronto quedó claro, seguían sufriendo. Habían resistido durante meses el asalto de Escobar y DeBoth, sí. Pero algunos temían que fuera sólo cuestión de tiempo que ellos también fueran desplazados.

[1] Para un analysis a profundidad de como lxs propietarixs sin escrúpulos utilizan a las Empresas de Responsabilidad Limitada como parte de su “maquinaria de desalojo” racista vea la tesis doctoral de Joel Montano titulada “Penetrando el velo corporativo del propietarismo de ERL: Una máquina depredadora de desalojos contra cuerpos negrxs y morenxs en los barrios obreros de los Angeles, 1996-2019”. El texto de la tesis está disponible en ingles.

El Departamento de Desalojo: Cómo la ciudad incentiva y facilita el desplazamiento

Es importante entender que el desplazamiento forzado que sufrieron los inquilinxs de Ave 55 a manos de Escobar, DeBoth y Alpine LA Properties es facilitado activamente por el sistema legal y el departamento de vivienda de Los Ángeles. Las instituciones que dicen proteger a los inquilinxs en realidad funcionan para certificar y lavar la violencia racializada de la gentrificación. Son herramientas para que los inversores inmobiliarios acumulen capital a través de la desposesión utilizando un proceso que existe únicamente para crear un barniz de justicia, un barniz que se resquebraja inmediatamente ante la más mínima investigación.

El caso del 249 S Ave 55 es un ejemplo demasiado típico de cómo funciona la acumulación sancionada por el Estado mediante el despojo. Al haber sido construido antes de 1978, el 249 S Ave 55 está cubierto por la Ordenanza de Estabilización de Alquileres de Los Ángeles (RSO por sus siglas en ingles), lo que significa que los inquilinxs del Ave 55 gozan de ciertas protecciones legales. Sus aumentos de alquiler están limitados a un 3-4% anual, una tasa que, aunque sigue siendo superior al crecimiento de los salarios y los precios, se sitúa muy por debajo de los exorbitantes aumentos de alquiler "a precio de mercado" que acompañan a la gentrificación. Hay un número bastante limitado de razones por las que un propietario puede rescindir el contrato de un inquilino RSO. Al igual que en otras ciudades de EE.UU. con protecciones de estabilización de alquileres, las unidades RSO ocupadas por inquilinxs de larga duración proporcionan esencialmente la única vivienda realmente asequible y estable en Los Ángeles.

Por supuesto, hay una trampa. La ampliación de las protecciones de la RSO a los edificios más nuevos no sólo está prohibida por la ley estatal Costa-Hawkins de 1995; la misma ley también estableció un vacío legal crucial en la Ordenanza de Estabilización de Alquileres de Los Ángeles: la prohibición del "control de vacantes". Cada vez que alguien se muda o es desalojado de una unidad de alquiler estabilizado en L.A., el precio estabilizado se desvanece y la unidad puede volver a colocarse en el mercado a cualquier precio. [2]

“las políticas e instituciones que dicen proteger a los inquilinxs en realidad incentivan, lavan y legitiman el lucro a través del despojo.”

La laguna de descontrol de vacantes no es un mero descuido en la política de estabilización de alquileres. Es una característica fundamental que hace que la estabilización del alquiler en su forma actual sea aceptable para los intereses inmobiliarios especulativos, y es precisamente la razón por la que Alpine LA Properties compró 249 S Ave 55. Cuando Alpine LA Properties compró la propiedad en el otoño de 2019, la mayoría de los inquilinxs predominantemente latinxs estaban pagando muy por debajo de la tasa de mercado del vecindario. Este rendimiento mensual comparativamente bajo es la razón por la que Alpine LA Properties pagaría $10,600,106 por el edificio—un precio demasiado alto si consideramos solo los ingresos que el edificio estaba trayendo en el momento de la compra, pero una ganga teniendo en cuenta el potencial de ganancias de la tasa de mercado del edificio. La adquisición por parte de Alpine LA Properties sólo tiene sentido desde el punto de vista financiero si se considera como una oportunidad de inversión para aumentar de forma inmediata y sustancial los ingresos por alquileres, eliminando a los 30 inquilinxs de largo plazo y sustituyéndoles por inquilinxs más ricos -y casi con toda seguridad más blancos- a los que se podría cobrar el precio vigente en Highland Park (2.000 dólares al mes por una habitación).

Es más, el actual sistema de estabilización de alquileres también proporciona el mecanismo legal por el que una empresa como Alpine LA Properties puede despojar rápidamente a los inquilinxs que supuestamente están protegidos por la RSO: el "acuerdo de desalojo voluntario". El Departamento de Vivienda e Inversión Comunitaria (HCID por sus siglas en ingles) de Los Ángeles permite a los propietarios hacer ofertas de compra a los inquilinxs de la RSO estableciendo cantidades mínimas (y totalmente insuficientes) de compra, cantidades que los propietarios pueden mantener como el precio autorizado por la ciudad para una unidad. Aunque la HCID se encarga aparentemente de comunicar a los inquilinxs que tienen el derecho absoluto de rechazar estas ofertas, esto casi nunca ocurre de forma efectiva.

Para los residentes que llevan mucho tiempo pagando un alquiler asequible muy por debajo del precio del mercado, verse obligados a aceptar un "acuerdo de desalojo voluntario" es un acontecimiento catastrófico, a veces mortal. Las ofertas de compra nunca son suficientes para que los residentes permanezcan de forma sostenible y segura en sus comunidades o, para muchxs el seguir manteniendo una residencia. Por eso las ofertas casi siempre van acompañadas del tipo de coacción y acoso que sufrieron los inquilinxs del Ave 55. De hecho, la necesidad de que esbirros como Escobar y DeBoth se encarguen del trabajo legalmente turbio y cínico de coaccionar a los inquilinxs para que abandonen sus casas ha creado una lucrativa industria artesanal en Los Ángeles denominada "re-arrendando". Un grupo de jóvenes "profesionales" a sueldo, hambrientos de ascender en la escala empresarial, han desarrollado las tácticas coercitivas necesarias para presionar a las familias para que abandonen sus hogares de 20, 30, 40 años. El HCID y la ciudad entienden todo esto. Sin embargo, pretenden que los inquilinxs de todo L.A. acepten estas ofertas de compra por su propia voluntad y, lo que es peor, que las ofertas constituyen una práctica económica "justa". [4]

De este modo, las políticas e instituciones que dicen proteger a los inquilinxs en realidad incentivan, lavan y legitiman el lucro a través del despojo. [5] Tras largos meses de apelaciones directas a los políticos locales y de campañas concertadas para trabajar a través de la HCID, que dieron pocos resultados, los inquilinxs de Ave 55 comprendieron que, en su lucha por defender sus hogares, las instituciones del Estado no eran simplemente neutrales. Estas instituciones eran socios activos y colaboradores en el desplazamiento de los inquilinxs.

[2] Otra laguna legal en el acta de Estabilizacion de Renta de los Angeles es el Acta Ellis fue publicada en 1985 como la primera reaccion a nivel estatal al movimiento de control de renta de los 1970. Del sitio del Sindicato de Inquilinos de los Ángeles: “La Ley Ellis es una ley estatal de California que permite a las personas propietarias desalojar a los y las inquilinas de unidades de renta estabilizada, si están planeando “´salir del mercado´.” La excusa pública para esta Ley es que protegería a pequeños propietarios que quieren retirarse. Pero en la práctica actual, la ley es usada casi exclusivamente por personas propietarias e inversionistas corporativos para desalojar, remodelar y revender los edificios que están bajo renta estabilizada. Entonces esas personas o demuelen edificios de renta estabilizada, los convierten en hoteles o apartamentos de lujo, o los anuncian ilegalmente como unidades disponibles en Airbnb.” Para darse una idea de la escala de devastación que el Acta Ellis a traido a Los Angeles, vea la poderosa presentación visual del Proyecto de Mapeo Anti-desalojo, de todos los 27,243 (y contando) desaljos desde el 2001 (en ingles).

[3] Tanto la proposición 10 (2018) y Proposición 21 (2020) hubieran revocado el acta Costa-Hawkins y por lo tanto le hubiera permitido a los municipios en california introducir (o reintroducir tal como es en el caso de Berkeley, Santa Monica, West Hollywood, East Palo Alto, Cotati, y Palm Springs) control de renta. Ambas propuestas fueron rotundamente derrotadas, en gran parte debido a las grandes sumas de dinero que la industria inmobilliaria (y en especial propietarios de Wall Street cómo el grupo Blackstone, Essex Property Trust, y Equity Residential) invirtió en su derrota. Para una lista de lxs 10 contribuyentes mas importantes en la campaña anti-proposicion 10. Para una historia un poco anticuada pero todavia extradordinariamente util sobre la historia de las luchas por el control de renta en California y luchas paralelas sucediendo en Massachusetts (en ingles).

[4] El Sindicato de Inquilinxs de Los Angeles produjo una “calculadora de adquisición” en el 2018 para demostrar lo descarado que son las ofertas de llaves por dinero. Incluso si ignoramos los gastos de mudanza y los aumentos en impuestos sobre los ingresos al aceptar la ofertas, los montos aprobados por el Departamento de Vivienda se van a esfumar en menos de dos años para la mayoría de Inquilinxs de bajo ingreso en Los Ángeles.

[5] Para un argumento similar sobre la forma en que la politica de “Vivienda Asequible” en realidad promueve la acumulacion de capital inmobiliario, vea el articulo de Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal titulado “La ficcion duradera de la vivienda asequible” (en ingles).

El infierno en la tierra: Las campañas de terror de Alpine LA Properties durante la construcción ilegal

En las semanas que siguieron a la primera reunión con los inquilinxs de la Ave 55, los miembrxs de NELo se dieron cuenta rápidamente de que el esfuerzo del propietario por desplazar a los inquilinxs de largo plazo no había terminado con la ola inicial de acoso de dinero por llaves. Había comenzado una segunda ronda de horror, en muchos aspectos más violenta que la primera. Poco después de que Alpine LA Properties expulsara a dos tercios de las familias de largo plazo, la empresa comenzó a realizar obras ilegales y no permitidas en las unidades recién vaciadas. Si bien era evidente que Alpine LA Properties quería reformar las viviendas desocupadas de la forma más barata y superficial posible para poder venderlas y volver a alquilarlas a precios más altos, la construcción ilegal también tenía el claro objetivo de aterrorizar a los inquilinxs restantes que aún no habían "aceptado voluntariamente" marcharse.

En vez de simplemente renovar a las unidades individuales, el equipo de construcción del propietario, sin permiso, destrozó el edificio, amontonando residuos peligrosos en los espacios públicos y probablemente liberando sustancias químicas tóxicas—incluyendo plomo y amianto—en el aire. Los trabajadores usaron de manera obvia sus herramientas eléctricas fuera de las viviendas de los inquilinxs por horas y horas sin ninguna razón aparente. En tres ocasiones distintas, hicieron agujeros del tamaño de una pelota de baloncesto en los techos de los baños de los inquilinxs del primer piso y esperaron semanas antes de parchear y limpiar. En el caso más violento, el equipo demolió el cuarto de baño de una familia latina, supuestamente para arreglar una tubería que goteaba, y luego se negó a reparar las paredes por meses, dejando a la habitación tan expuesta a los elementos que enjambres de cucarachas y familias de ratas invadieron el apartamento.

El mensaje era inequívoco: si aún no has aceptado un acuerdo "voluntario" de desalojo, vamos a hacer de tu hogar un infierno terrenal hasta que lo hagas. La administración no ocultó sus intenciones. Cuando una de las parejas, nuevas, blancas y gentrificadoras llamó al propietario para quejarse de la infiltración de cucarachas en su unidad durante la construcción, el encargado de mantenimiento le dijo: "¿En qué unidad está usted? Ah, claro, usted es uno de los que queremos mantener". Cuando la inquilina latina cuyo baño fue destruido se quejó repetidamente de que las reparaciones estaban tardando demasiado, Ángel Escobar volvió a decirle que las reparaciones no eran prioritarias y que podía mudarse si quería mantener a su familia segura y sana.

“El mensaje era inequívoco: si aún no has aceptado un acuerdo “voluntario” de desalojo, vamos a hacer de tu hogar un infierno terrenal hasta que lo hagas.”

La Asociación de Inquilinos: De la crisis al poder comunal

Cuando los inquilinxs de Ave 55 formaron su asociación de inquilinxs (AT), estos fueron los problemas contra los que se unieron para enfrentarlos. Junto con los miembros de NELo, crearon un hilo de texto bilingüe para todo el edificio y empezaron a convocar reuniones semanales bilingües en su patio, compartiendo sus historias, conociendo las vidas y experiencias de los demás y elaborando estrategias conjuntas sobre cómo abordar sus problemas de habitabilidad y el continuo acoso de Alpine LA Properties. Los éxitos concretos del AT fueron inmediatos.

En pocas semanas, aprendieron a navegar por la complicada burocracia municipal para presentar denuncias, explotándola para sus propios fines con el fin de retrasar y complicar la construcción ilegal de Alpine LA Properties.

Cuando Escobar y DeBoth amenazaron a un inquilino latinx discapacitado desde hace mucho tiempo con el desalojo ilegal, los miembros de TA utilizaron el hilo de texto para organizar una vigilancia del desalojo las 24 horas del día que culminó en una confrontación exitosa; los agentes de Alpine LA Properties fueron rechazados por un grupo de inquilinxs que bloquearon físicamente la puerta de su vecino.

Los inquilinxs colocaron carteles de "Protegidos por SILA" en sus ventanas, comunicando visualmente su unidad y solidaridad, y comenzaron a enfrentarse colectivamente a los posibles inquilinxs que visitaban la propiedad. Explicando las prácticas de Alpine LA Properties y las condiciones del edificio a los posibles inquilinxs, a menudo frente a un agente de arrendamiento de Alpine LA Properties balbuceante e indignado, la asociación consiguió mantener la mayoría de las unidades renovadas sin ocupar durante muchos meses.

Estas creativas estrategias organizativas ejercieron una presión material sobre Alpine LA Properties y la obligaron a ceder a las demandas de los inquilinxs. En marzo de 2020, los inquilinxs de Ave 55 organizaron su propia campaña de difusión, colocando carteles en el exterior de su edificio y en todo el barrio, anunciando su presencia y ofreciendo solidaridad y apoyo a sus vecinos.

La Asociación de Inquilinxs de Ave 55 ha forjado una solidaridad y una comunidad poco común entre un grupo de inquilinxs en su mayoría, gentrificadores, jóvenes, multirraciales, y sus vecinos latinxs que han residido en el edificio por décadas. Las crisis de habitabilidad compartidas unieron a inquilinxs de diferentes orígenes. Pero, sólo a través de la construcción de una verdadera amistad con sus vecinos latinos de clase trabajadora, los inquilinxs gentrificadores comenzaron a entender tanto su complicidad en la violencia de la gentrificación como su interés colectivo en poner fin a esa violencia. Después de todo, la violencia de la gentrificación y los intereses del capital inmobiliario dependen de la suposición de que los inquilinxs gentrificadores—la mayoría de los cuales están agobiados por alquileres, deudas y son efectivamente de clase trabajadora, aunque se les anime a imaginarse a sí mismos de otra manera—nunca reconocerán sus intereses compartidos ni se solidarizarán con los inquilinxs de largo plazo, los inquilinxs sin vivienda, otros grupos desposeídos e migrantes. En este sentido, algunas de las actividades más radicales desarrolladas por la Asociación de Inquilinxs de la Ave 55 pueden ser las aparentemente mundanas, los pequeños hábitos comunitarios que han empezado a forjar relaciones duraderas entre clases y razas.

En medio de esta poderosa organización a nivel de edificio, la Asociación de Inquilinxs de la Ave 55 y sus socios de NELo hicieron un importante descubrimiento: Alpine LA Properties poseía otras veinte propiedades en Los Ángeles. Al igual que el 249 S de la avenida 55, la mayoría de estas propiedades eran edificios de la RSO en barrios en proceso de gentrificación que habían sido adquiridos el año anterior.

Lo que está en juego en el desplazamiento: la gentrificación como limpieza social

A menudo se ha observado que—con una lógica irónica llena de potencial radical—determinadas formas de explotación y opresión crean las condiciones para formas específicas de lucha transformadora. En el caso de Alpine LA Properties y de la práctica de la especulación inmobiliaria en general, la adquisición selectiva de edificios similares en todo Los Ángeles sembró la semilla de la solidaridad masiva entre edificios, aunque esta semilla requirió (y requiere) una alimentación intencionada y organizativa para florecer.

Michael & Nathan Kadisha

Después de indagar un poco, los inquilinxs de Ave 55 y sus socios de NELo descubrieron que detrás de Alpine LA Properties había dos hermanos gemelos de 20 años, Michael y Nathan Kadisha, y un tercer joven Kadisha llamado Joshua. A través de su relación con el magnate de las telecomunicaciones y multimillonario inversor Neil Kadisha, Michael y Nathan son los herederos de una vasta fortuna invertida ahora en gran parte en el sector inmobiliario. La familia Kadisha también es propietaria de Omninet Capital, que controla más de mil millones de dólares en activos inmobiliarios comerciales y 13.000 unidades residenciales en todo el país. Es probable que su imperio se extienda aún más: los Kadishas están conectados por matrimonio con la acaudalada familia Nazarian, conocidos inversores, "filántropos" y empresarixs con participaciones igualmente extensas.

“Lo que está en juego en el desplazamiento es la vida y la muerte.”

Alpine LA Properties realizó su primera compra en Los Ángeles en 2016: un edificio de 4 plantas y 32 unidades con fachada de ladrillo en una zona gentrificada de Koreatown. Ocho meses más tarde, la empresa adquirió una segunda propiedad, un complejo de 4 unidades en el barrio gentrificado de Boyle Heights. A continuación, tres propiedades más en Boyle Heights. Luego otras dos en Koreatown. Luego un edificio en Highland Park. Otro en Koreatown. Dos más en Highland Park. Otro frenesí de compra mientras la pandemia del COVID-19 asolaba los barrios obreros: diez edificios en Koreatown, lo que elevó su cartera de Los Ángeles a al menos 21 propiedades (que sepamos).

Desde que descendieron a Los Ángeles en 2016, los hermanos Kadisha, recién salidos de la universidad, han invertido más de 120 millones de dólares en inmuebles residenciales.

Es importante apreciar la escala completa—y la lógica brutal y racista—de la devastación que Alpine LA Properties y los hermanos Kadisha han provocado en las comunidades donde compraron edificios. Un retrato parcial de esta devastación emerge cuando examinamos los registros de la HCID disponibles públicamente de los "acuerdos de desalojo voluntario" realizados en las propiedades de Alpine LA Properties. Aunque la HCID sólo registra los "acuerdos" que se presentaron oficialmente a la ciudad y, por lo tanto, no incluye las numerosas ofertas de compra ilegales y no declaradas de Alpine LA Properties ni otros desalojos ilegales -incluidos los "autodesalojos" logrados por la falta de reparaciones, el acoso y la explotación de la mayor precariedad de los inquilinxs durante la pandemia-, las cifras siguen siendo abrumadoras. De los registros oficiales de la HCID:

3048 West 12th Street: entre octubre de 2019 y enero de 2020, 9 compras

437 North Ardmore Avenue: entre diciembre de 2019 y mayo de 2020, 58 compras

249 South Avenue 55: entre julio de 2019 y marzo de 2020, 20 compras

941 South Kenmore Avenue: entre noviembre de 2020 y enero de 2021, 7 compras

915 South Kenmore Avenue: entre noviembre de 2020 y enero de 2021, 4 compras

200 South Kenmore Avenue: entre noviembre de 2020 y enero de 2021, 12 compras

410-414 South Manhattan Place: entre junio de 2020 y enero de 2021, 15 compras

727 South Mariposa Avenue: entre octubre de 2020 y noviembre de 2020, 29 compras

975-985 South Oxford Avenue: entre diciembre de 2019 y enero de 2020, 8 compras

207 North Oxford Avenue: entre mayo de 2020 y agosto de 2020, 4 compras

Entre Julio 2019 y Enero 2021—a lo largo del catastrófico aumento de casos de COVID-19◊Alpine LA Properties desplazó a inquilinxs de 166 unidades usando “formas legales” de compra de llaves por dinero. Si asumimos que en una familia promedio de 2.8 personas—aunque el tamaño de la familia con toda probabilidad era más alto, dado las formas en que las personas de bajos recursos son forzadas a compartir espacios limitados para poder sobrevivir—Alpine LA Properties desplazó violentamente cerca de 465 personas en año y medio, usando intencionalmente la angustia resultante de la pandemia del COVID-19 para acelerar sus esfuerzos. Igual que les inquilinxs de la 249 S. Ave 55, la gran mayoría de estas personas eran Latin-x, muches de elles indocumentades, y muches habían perdido trabajo, perdido ingresos o luchado contra enfermedades. Este es el modelo de negocios de los Hermanos Kadisha, uno que es demasiado común en L.A: sistemáticamente identificar edificios en RSO “de poco rendimiento” para después limpiar esos edificios de las personas de bajos ingresos, que son predominantemente familias Latinas para poder volver a rentar las unidades vaciadas para obtener un lucro masivo.

“Para que Alpine LA Properties pueda hacer dinero, niñes tienen que ser arrancades de sus escuelas y sus redes de amistades. Madres y padres de bajos recursos tienen que ser arrancades de sus redes de supervivencia y relaciones de toda la vida.”

Esta práctica solo puede ser descrita como limpieza social. En la imaginación popular, los terminos “limpieza social” y “genocidio” están asociados con imagenes de sepulturas masivas, mientras que el termino “gentrificacion” meramente trae a la mente cafeterias hipster, cafes lates caros, fazadas renovadas. De hecho, los agentes de bienes raíces usan el término “gentrificación” casi con alegría como un punto para poder hacer la venta. Pero es crucial entender que genocidio y gentrificacion, son de hecho, inseparables.

Para que Alpine LA Properties pueda hacer dinero, niñes tienen que ser arrancades de sus escuelas y sus redes de amistades. Madres y padres de bajos recursos tienen que ser arrancades de sus redes de supervivencia y relaciones de toda la vida, que incluyen trabajo, cuidados de salud, familias extendidas, iglesias, círculos de cuidado de niñes, clubes sociales, comunidades. En el análisis final, la gente tiene que morir para que Alpine LA Properties obtenga ganancias.